Alive, she cried: What happens to ‘Frankenstein’ when you revive it with women in charge?

Screenwriter Diablo Cody has been in Hollywood long enough that she doesn’t believe in coincidences.

“Not to get woo-woo, but having worked in this industry for 20 years, I do believe there is a collective creative consciousness because I’ve seen this happen so many times where suddenly a bunch of similar projects will surface,” she says. “None of it was ever intentional, but there’s a vibe.”

That vibe could be famously competing asteroid movies (“Armageddon” and “Deep Impact,” both from 1998) or, for that matter, competing volcano movies (“Volcano” and “Dante’s Peak” in 1997). But right now, the idea in the ether is Frankenstein. Specifically, Frankenstein with a female bent.

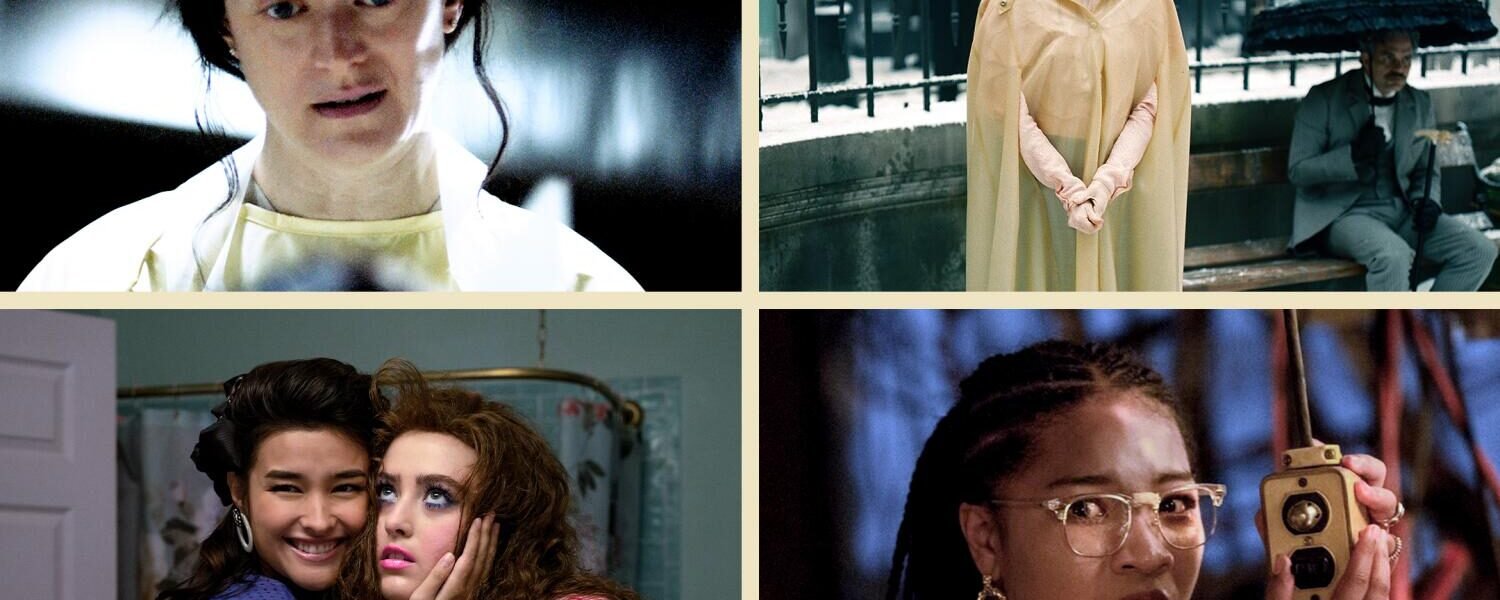

In Cody’s case the movie is “Lisa Frankenstein,” an ’80s-set horror-comedy in which a lonely teenage girl, Lisa (Kathryn Newton), finds herself face to face with the reanimated corpse of a 19th century dreamboat (Cole Sprouse) she’s been fixating on in the local cemetery. He needs body parts and she can help get those for him, zapping him further back to life with the electrifying tanning bed in her garage. Director Zelda Williams calls Lisa’s creature her “own personal violent Mr. Darcy zombie.”

And that’s just the latest example. There’s also the Oscar-nominated “Poor Things,” based on Alisdair Gray’s novel in which the creature, not the creator, is a woman named Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), a former suicide victim revived with the brain of her unborn child.

On top of that, last year we saw the release of two indies with similar themes. There’s “birth/rebirth” from filmmaker Laura Moss, in which an off-puttingly antisocial morgue technician, Rose (Marin Ireland), obsessed with bringing the dead back to life, steals away with the corpse of a young girl only to have the child’s mother, a nurse (Judy Reyes), join her in co-parenting the undead. Meanwhile, Bomani J. Story’s “The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster” finds a teen heroine (Laya DeLeon Hayes), frustrated by the violence in her community, bringing her murdered brother back to life through technology she assembles behind a door that reads “Condemned: Extreme Electrical Hazard.”

After all of that, the trend isn’t going to stop: “The Lost Daughter” director Maggie Gyllenhaal is reportedly tackling a rethink of “Bride of Frankenstein” for Warner Bros. with Jessie Buckley and Christian Bale. (Gyllenhaal was not available for comment.)

So why is Frankenstein all the rage? “I think the time has come,” Cody offers, adding that at this moment, female voices who have been longing to tell these tales have more power to do so. “Like, why do we not have Frankenstein stories from the female perspective? Maybe they all need to be unleashed and I’m going to see them all.”

Director Moss has a slightly opposing read on the confluence of films. “They all feel like they are using the Frankenstein mythology to explore different themes, so I’m not sure it has to do with a larger societal Frankenstein moment as much as it’s a really robust myth,” Moss says.

Judy Reyes, right, and Marin Ireland in the movie “birth/rebirth.”

(Shudder)

And, of course, that myth originated with a woman, Mary Shelley, who, at 18, first wrote the story of Victor Frankenstein and his creature when prompted by Lord Byron, during a rainy stretch indoors, to come up with a “ghost story.” Both Story and Moss started building their films from deep personal interest in Shelley. Story calls Shelley the “queen,” and his inspiration for the character Vicaria, who is called “mad scientist” by people in her neighborhood, came from multiple sources including Shelley, his own sisters, Black women he saw organizing in the Black Lives Matter movement and legendary activists like Angela Davis and Tamika Mallory.

Moss explains that her protagonist Rose, who conducts reanimation experiments in her grim New York City apartment, was imagined as a “fusion” of Shelley and Shelley’s on-the-page creation, Dr. Victor Frankenstein.

In the years since Shelley’s novel “Frankenstein” was first published in 1818, the text has been remixed countless times, especially for the screen — from James Whale’s indelible 1931 feature starring Boris Karloff to 1990’s “Frankenhooker,” the exploitation comedy about a man who uses the body parts of prostitutes to revive his dead wife. It’s a film that Williams revisited when preparing “Lisa Frankenstein.”

“Because we’ve lived with it so long, it just becomes a bit more easy to start shifting it and changing it,” says Kieran Foster, a scholar at England’s University of Nottingham who has studied the Hammer Studio Frankenstein films. “The rich metaphors that [Shelley is] using in her original story about man and God, creation and evolution, are quite radical at the time, so what you end up with is a kind of punchy premise that is actually allegorical and telling a much wider, epic scope.”

If “Frankenstein” was originally a story about a man playing God, written by a woman, it becomes a bit more complicated when you introduce a person who is naturally able to conceive life without the use of chains, pulleys and a lightning bolt. And while, as Moss says, all of these new spins on “Frankenstein” are using the central ideas to tell various narratives, they all in a way grapple with different questions of bodily autonomy.

Emma Stone and Mark Ruffalo in the movie “Poor Things.”

(Atsushi Nishijima / Searchlight Pictures)

In “Poor Things,” directed by Yorgos Lanthimos and adapted by Tony McNamara, there is a male creator (Willem Dafoe) named Godwin — Shelley’s maiden name, but called “God” in the film — who believes he can contain Bella. Instead, Bella seizes control of her body through a series of sexual adventures, ultimately feeling most at home in an operating room herself, becoming a scientist by the movie’s end.

Moss’ “birth/rebirth” takes its exploration of a woman’s body to an even darker place. Rose fuels her scientific work through self-induced miscarriages, a nod to Shelley’s own history with prenatal complications.˜(The author Jill Lepore once wrote in the New Yorker: “‘Frankenstein’ is four stories in one: an allegory, a fable, an epistolary novel and an autobiography, a chaos of literary fertility that left its very young author at pains to explain her ‘hideous progeny.’”)

“When I started really exploring that gender-flipped concept in earnest, it became obvious to me that if you have a character with a uterus, it would be a shame not to address how that might play into their science and their creation,” Moss says. “As I, over the course of my 20s and 30s, went through my own gender journey, I think it’s really interesting now to think about gender as a construct and maybe all of us as monsters constructed by rigid gender norms. What is the creature? Who is the monster? These are really fundamental questions that I think you could take in so many different directions.”

“Lisa Frankenstein,” on the surface, is a much goofier approach to the original material, but there are similar (and equally serious) themes coursing through it.

Initially, Cody heard Universal was looking for a new “Bride of Frankenstein.” “I sat down and wrote basically the entire outline to this movie and quickly realized this is not Universal’s ‘Bride of Frankenstein,’” she says. “This is like my own weird-ass sort of reinterpretation of that mythology.”

(Michele K. Short / Focus Features)

While Cody was a fan of Whale’s “Bride of Frankenstein,” she also took inspiration from John Hughes’ 1985 comedy “Weird Science,” about dorks building a dream girl. Cody’s handsome Creature was inspired less by Boris Karloff and more by “having grown up madly in love with ‘Edward Scissorhands,’” specifically Johnny Depp’s loner hero. Cody, who won an Oscar for 2007’s “Juno,” was also eager to embark on another paranormal project thanks to the critical reclamation of “Jennifer’s Body,” her 2009 teen-possession script directed by Karyn Kusama.

And yet at the same time, Lisa is a girl dealing with extreme grief following the gruesome murder of her mother, and, in an early scene, is sexually assaulted by a peer. She and the Creature eventually conspire to lop off that grabby assailant’s hand to replace a decaying limb. “The emotional key to the story was realizing that she’s not just creating for the sake of creation or because she has a god complex or anything like that,” Cody says. “She’s repurposing these parts in a way that makes sense to her and heals her.”

Cody admits that Lisa herself isn’t the most likable person. She has the self-centeredness of so many of those who mess with the natural order of things, and ignores some of the Creature’s own needs to use him for her benefit. But she’s also processing her sadness. “It’s about a woman learning to navigate grief at its core, which I know all too well,” says Williams, who dealt with that topic in a very public way following the death of her father, Robin Williams.

And Lisa is allowed to be something of a monster herself as she overcomes that all-consuming sorrow. In black lace and red lipstick, she embarks on a mission not only to take down those who wronged her but also to lose her virginity. “It was more about her coming into a more monstrous version of herself, but in the pursuit of autonomy and confidence and outward expression of grief,” Williams explains.

Grief also looms over “The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster.” Vicaria’s experiment is a response to the deaths of both her mother and her brother. It’s there in “birth/rebirth” too. Judy Reyes’ grieving mother Celie becomes a participant in Rose’s work to help keep her daughter Lila (A.J. Lister) alive.

And it’s there, of course, in the original text as well, if not in some of the other cinematic interpretations. In Shelley’s version, Victor is mourning his mother as his experiment begins, and he describes that pain in vivid detail. “When the lapse of time proves the reality of the evil,” he says in the book, “then the actual bitterness of grief commences.” Victor continues to grapple with loss as his monster enacts revenge by killing his loved ones.

It’s perhaps proof that everything old is new again. Or that these adventurous filmmakers are reinventing “Frankenstein” by bringing it back to its roots. These monsters and creators may wear skirts and have ovaries, but they are not all that distant from their literary ancestors. In a way they are reclaiming Shelley’s creation myth for women, letting them be mad geniuses — with the connotations, bad and good, that would imply — be they mothers, loners or teens with tanning beds.