A threat by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen to destroy internet infrastructure traversing the Red Sea may not be enough to destabilise the internet across the region, experts have said.

The Guardian and other news outlets on Monday reported that telecommunications firms linked to the Yemeni government fear that Houthi rebels off the coast are threatening to destroy undersea cable infrastructure connecting parts of the Middle East, Africa and much of Asia to the Western world.

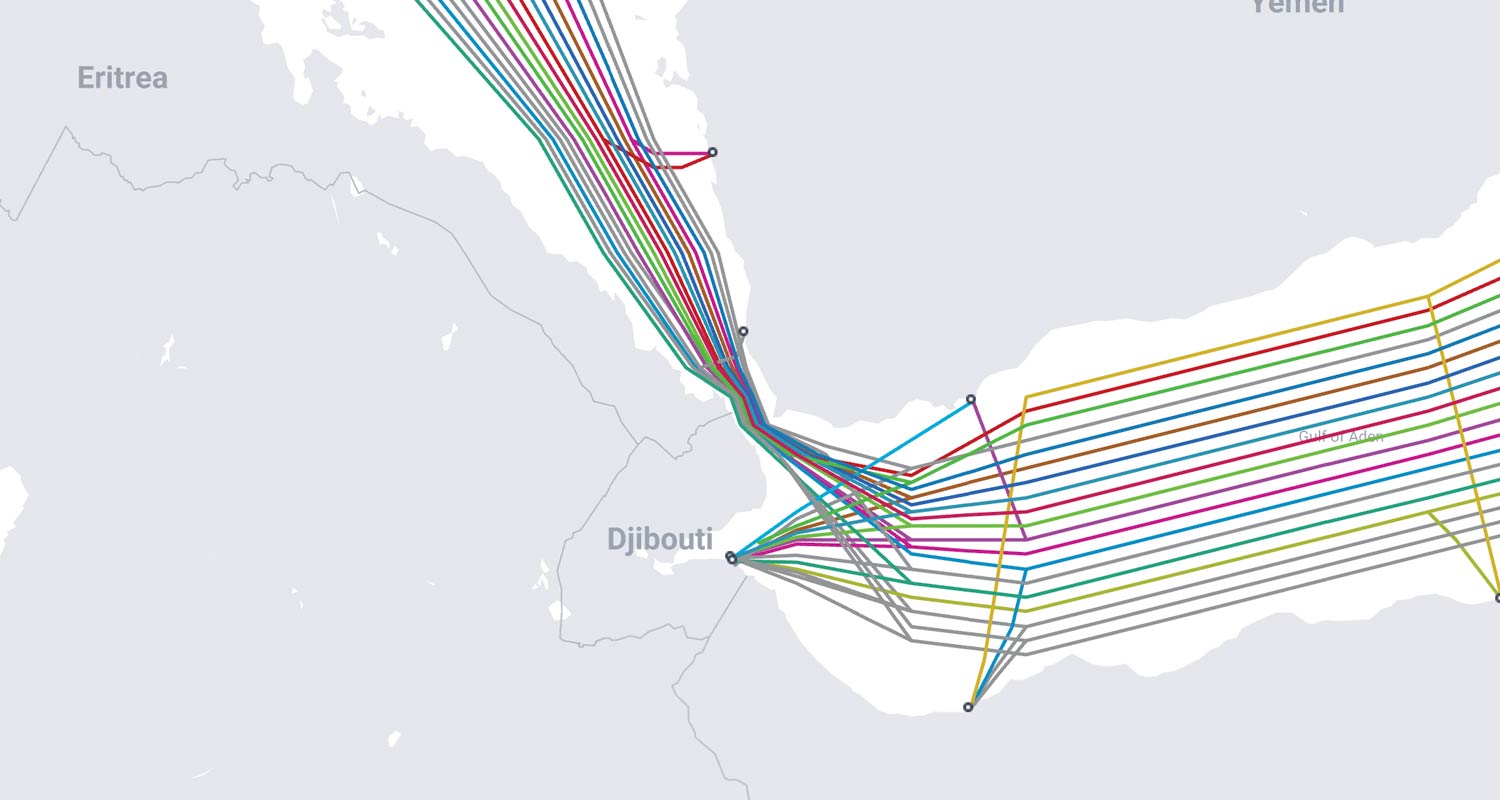

Apart from being one of the world’s busiest shipping corridors, the Red Sea is also host to some of the world’s biggest intercontinental subsea cables, including several that run along Africa’s east coast.

The news reports about a potential attack on the subsea cables come after a Houthi-linked Telegram channel published a map of the cables running through the Red Sea along with what has been interpreted as a veiled threat.

“There are maps of international cables connecting all regions of the world through the sea. It seems that Yemen is in a strategic location, as internet lines that connect entire continents – not only countries – pass near it,” it said.

But how significant is the threat of sabotage to undersea cables in the Red Sea to the stability of the internet globally? And should Africans be concerned about potential disruptions?

“There are approximately 20 submarine cables running in the vicinity of the Red Sea. The area is a major hub for transporting internet traffic between Asia, Africa and Europe, and accounts for about 17% of the world’s internet traffic,” Prenesh Padayachee, group chief digital officer at Seacom, told TechCentral.

Densely packed

Although undersea cables are often hundreds of kilometres apart, the cables that run through the Red Sea are densely packed through a narrow, 26km passage between Yemen and Djibouti called Bab al-Mandeb (the Gate of Tears). The seabed is elevated in this region, so cables are as high up as 100m below sea level as opposed to their average 400m depth elsewhere.

The concentration and heightened level of exposure of the cables make this region particularly vulnerable to attack. “It is likely the location with the greatest complexity and risks associated with subsea cable systems,” said Padayachee.

But the narrow Gate of Tears region is protected by military bases on either side, decreasing the likelihood of an attack going unnoticed. Regions further west along the Yemeni border may be easier to infiltrate, but the 20mm cables (the size of a thick hosepipe) are spread far apart there and the seabed is lower, too.

Read: New internet cables save South Africa’s bacon

Not all parties are convinced that the threat is real. In a December statement, the Yemeni telecommunications ministry criticised media reports suggesting that undersea cable infrastructure was at risk of attack.

“The ministry of telecommunications & information technology disclaims what has been published by social and other media with regard to threats against the submarine cables that cross Bab al-Mandeb in the Yemeni Red Sea,” said Teleyemen, a state-owned telecoms company, in a statement.

As security analysts in the region analyse the threat level, what is clear is that the potential consequences of a successful attack against the internet infrastructure in the region poses a risk to internet users further afield.

Undersea cables are often subjected to damage when ships mistakenly drop their anchors onto them. Seismic events on the ocean floor are another cause for concern, and are suspected to be the cause of breakages to the Wacs, Sat-3 and Ace cables off the coast of the Democratic Republic of Congo in August 2023. As South African internet users experienced at the time, a drop in the availability of undersea cable capacity leads to increased latency and a poorer browsing experience.

But the cables in the Red Sea are more numerous and have far more capacity than those along the west coast of Africa, meaning more countries and people would be affected. Cables passing through the narrow sea include the world’s longest subsea system, Sea-Me-We-3, which connects Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Western Europe.

Internet users in Dubai, for example, would have no choice but to route their data traffic to Europe around Africa or Asia, increasing latency. All the traffic from Asia and Australia heading to Europe would also have to be diverted in this way. But South Africans, according to Padayachee, have little to worry about.

“The risks vary depending on the location. In a scenario where multiple subsea cables in the Red Sea were to be disrupted, the routing from Southern Africa would largely depend upon connectivity and capacity via Africa’s west coast systems, as well as the reciprocal backhaul capacity across Europe,” he said.

Another point to consider is that much of the capacity available on the larger, newer cables such as Equiano on Africa’s west coast is not necessarily being used. This is true for many undersea cables around the world. In the event of a severe disruption, this capacity would be made available to pick up any slack in the system.

Read: Google’s giant Equiano Internet cable has landed in South Africa

“In the short term, some capacity imbalances may likely be anticipated until such time that reciprocal capacity can be brought into production to compensate for losses. Although there would be major disruptions to internet traffic, there are alternative paths,” said Padayachee. – © 2024 NewsCentral Media

Meet the Sophie Germain: R1-billion ship will help fix African subsea cables