Payers are always wary about funding new treatments for illnesses and conditions: When millions of dollars are at stake, payers want demonstrated improvements in outcomes. So do doctors and patients, before they go through the trouble of adopting a course of treatment. So there was much consternation recently when the Peterson Health Technology Institute (PHTI) released a report saying that digital interventions weren’t helping people with diabetes much and weren’t worth their added costs.

PHTI has a comprehensive and detailed assessment framework that it applies to health care technologies to determine whether they demonstrate clinical effectiveness and cost savings. I exchanged some emails with PHTI about their diabetes report. I also talked to representatives from two companies listed in the report—one of which actually received a passing grade for improved outcomes—and with Andy Molnar, CEO of an industry consortium called the Digital Therapeutics Alliance.

Some Basics About the Report

PHTI did a typical literature review, evaluating a wide range of published studies and combining their conclusions. Their rigorous standards identified 1,139 possible studies but eliminated all but 49 in the end. These studies are listed in the appendices, along with other details.

Solutions that use constant glucose monitoring (CGM) were categorically excluded from the report, although it says, “The increasing use of GLP-1 medications and CGMs represent important opportunities for review and innovation.” PHTI justified the exclusion because this expensive form of monitoring isn’t yet covered by many payers (and notably not by Medicaid and Medicare). But everyone understands that CGM could radically transform the course of diabetes in the future; I’ll return to that idea at the end of the article.

The report tried to answer two questions: whether clinical outcomes for diabetes improved, and whether the costs were worth the change. To be considered successful, a digital intervention would have to reduce patients’ A1C better than “usual care.” (The report refers to the test as hemoglobin A1C, or HbA1c.)

The report then used estimates from the clinical literature to estimate the savings that payers would enjoy from improved A1C measures, and also estimated the costs of digital interventions. The report contains a lot of detail about how they tried to compare digital solutions to usual care in a fair manner.

All the interventions showed some improvement in outcomes (see page 40 of the report). People starting out with high A1C measures were helped more than those with lower A1C, showing that the patients most in need of help were better served. But when extra costs were considered, PHTI concluded that most interventions weren’t financially worthwhile.

The report explicitly evaluates only eight companies, but as a PHTI representative said, “We drew upon an evidence base to which many other companies contributed over the past decade. Many solutions have a similar mechanism for engaging patients and providers and, given the consistency of results across the body of evidence, these solutions are likely to produce similar results.”

Regarding the choice of eight companies mentioned explicitly, the representative said, “We focused on solutions that have sufficient funding, are being actively considered by purchasers, and have sufficient category-level evidence to assess.” But only six of the eight companies do behavior and lifestyle modification. Glooko was described as offering simply remote patient monitoring. Virta, which will be examined in the following section, was the only company to receive a positive rating.

Where did evidence come from? PHTI approved studies for Dario, Glooko, Livongo, Omada, Vida, Virta, and some miscellaneous interventions. They also received submissions of findings from Dario, Omada, Perry Health (although it was not listed in the appendix of results), and Virta. Apparently, they also included an eighth company, Verily, because of “similarities in solution design” to Perry Health.

Virta’s Low-Carbohydrate Strategy

Interestingly, Virta is not primariily a digital health solution. The company helps members adopt a low carbohydrate diet. When you sufficiently reduce your intake of carbs, the fat in your body contributes energy, leading to a reduction in fat. The process is called ketosis and is the basis of popular “Keto” diets, although Kevin Kumler, President of Virta Health, tells me that Keto is a vague term; it can take on a range of meanings, much the way “lite” foods did in the 1980s.

Virta bases its behavioral changes on a personal interaction between a client with diabetes and a coach. They have been in business for almost ten years, and now offer their service to people who have successfully taken off weight and improved their condition through medication. Instead of continuing with expensive GLP-1 drugs after achieving their target weight and AiC, Virta can provide an “offramp” for patients to maintain their lower weights without their medication, which is otherwise very hard to do.

Digital technologies do play an important role in Virta’s strategy. Besides the telehealth visits between patient and coach, the technologies track the usual vital signs (weight, glucose, ketones) and send alerts if either the patient or the coach don’t report results regularly. Still, it seems to me that Virta is more of a technology-enabled coaching and diet control solution than a digital intervention.

Criteria and Criticisms

Those who criticized the PHTI report expressed approval that PHTI carries out evaluations like this one. But they argued that this PHTI report was ignoring or filtering out important evidence of digital interventions’ success.

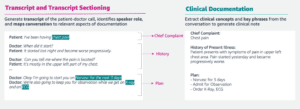

Literature reviews are an important fixture in science and medicine, but leave out details that can make an important difference. Exhibit 11, on page 24 of the report, illustrates the kind of summarization the PHTI performed: number of subjects in each study, the reduction in HbAIC compared to usual care, etc.

Somehow, even though the report cites Dario Health for a 23.5% reduction in hospitalizations among its clients (on page 28 of the report), Dario did not benefit from that achievement in the report’s rating. What other valuable accomplishments are missing?

A PHTI representative wrote to me, “We focused on studies with an appropriate comparator to show outcomes for users of the digital solution and how those outcomes compare with other treatment options.”

As I mentioned earlier, the interventions all achieved moderate successes, which people with diabetes would consider valuable. PHTI, however, considered only the interests of payers by balancing successful treatments with estimated costs and financial savings.

Hazel Nugent, vice president of business development at the Digital Therapeutics Alliance, focused on the estimation of costs, and pointed out that actual costs and savings (real-world evidence) have been recorded for some interventions. Dr. Omar Manejwala, chief medical office at DarioHealth, says, “PHTI categorically excluded all studies of digital health cost reductions that provided comparative studies of actual claims reductions. Instead, they employed a less trustworthy estimated cost model.”

The PHTI representative answered that many of the studies they examined were derived from real world evidence, and added, “We used the cost and pricing data that was made available to us by companies and via published figures. This reflects the best information available to us by the time of publication. In addition, we reviewed independent economic studies, third party financial analyses, and company healthcare cost utilization studies where available. All sources, including company studies, are estimates from selected samples of patients with or without appropriate comparators. Put another way, they are estimates as well.”

Including Glooko was unjustified, if indeed it is just a remote patient monitoring service as described in the report. Monitoring is used by virtually all solutions, but is not an intervention in itself. It provides data that might be useful, but one must act on data to turn it into an outcome.

On the other hand, the benefits of one type of monitoring—continuous glucose monitoring—are producing excitement in the diabetes community. Traditionally, a patient was supposed to prick his finger once or twice a day and make nutrional decisions for the rest of the day on the basis of the results. This was a lot to expect of people, and was of fundamentally limited value because of the hours-long gap between obtaining results and acting on them.

In contrast, CGM provides instant results, and digital solutions can make immediate recommendations. Both the treatment itself, and adherence to treatment, are likely to improve dramatically and demonstrate the value of digital interventions.

What to Do Next

The Digital Therapeutics Alliance would like to consider this PHTI report as just a first pass. The experience of companies in the digital space suggests that further investigation will turn up more successes. Molnar wishes that PHTI would announce results at forums, as CMS does, in order to promote a dialog with affected stakeholders. He feels that publicists at PHTI seized on sensational aspects of the report to create a strong impression.

I hope that this article encourages people to read the PHTI report and evaluate what it offers to digital companies and those treating diabetes.

Get Fresh Healthcare & IT Stories Delivered Daily

Join thousands of your healthcare & HealthIT peers who subscribe to our daily newsletter.