The Women’s Health Gap Is Especially Wide During Her Working Years – Learning from McKinsey, the World Economic Forum, and AARP in Women’s History Month

There’s a gender-health gap that hits women particularly hard when she is of working age — negatively impacting her own physical and financial health, along with that of the community and nation in which she lives.

March being Women’s History Month, we’ve got a treasure-trove of reports to review — including several focusing on health. I’ll dive into two for this post, to focus in on the women’s health gap that’s especially wide during her working years. The reports cover research from the McKinsey Health Institute collaborating with the World Economic Forum on Closing the Women’s Health Gap; and, from AARP in their paper titled, 2024 She’s the Difference – The Wildcard of the 2024 Election. Together, these reports speak to the more overlooked area of women’s health between her age span of 20 to 64 years.

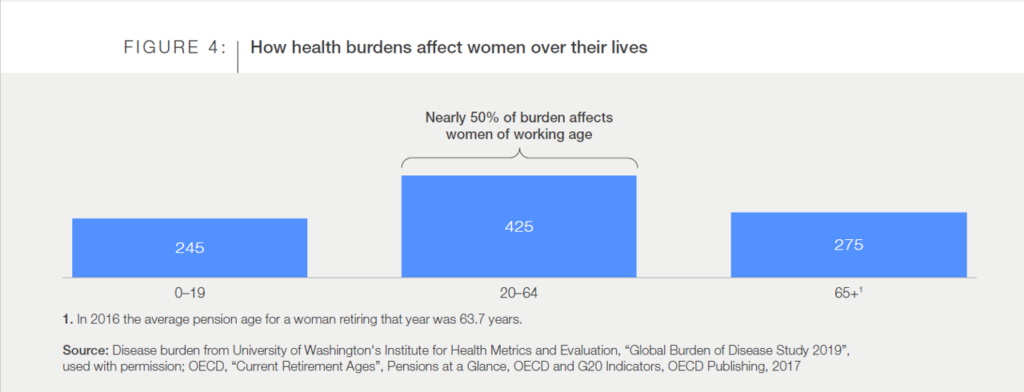

The bar chart illustrates three chapters in a woman’s life: from birth to 19 years of age, 20 to 64 years, and 65 years and over. That middle pillar here illustrates that nearly 50% of health burdens affect women in the years, generally speaking, in which she could earn a living. McKinsey and team have considered data from U-Wash’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation on the global burden of disease, coupled with OECD data on retirement ages — for the latter, finding that the average pension age for women in 2016 was 63.7 years.

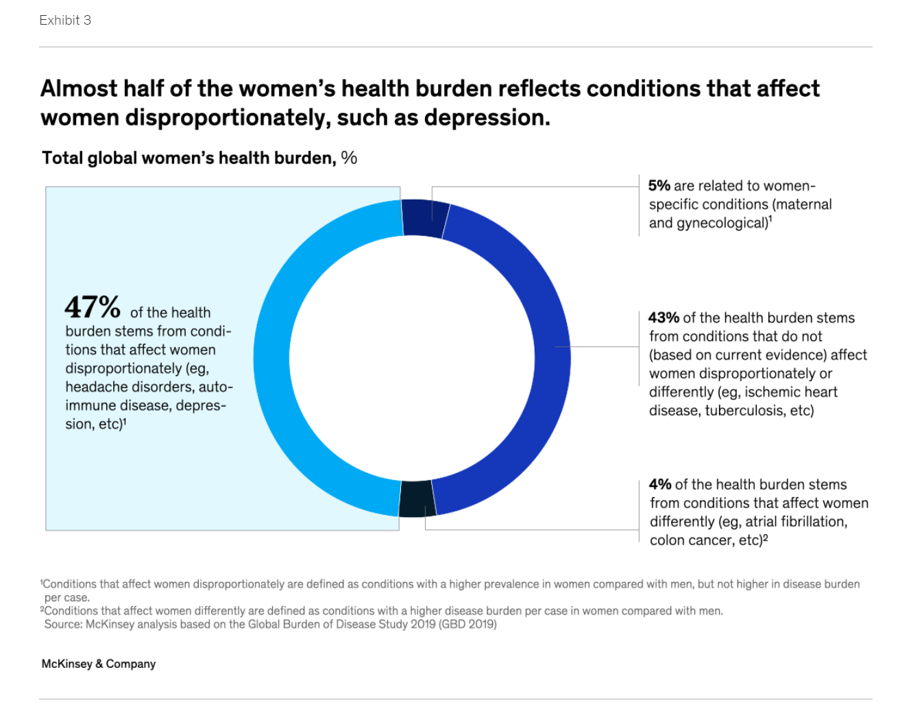

From the general to the specific, here we learn that nearly one-half of women’s health burden falls into conditions that impact women disproportionately: these include auto-immune disease, depression, and headache.

Taken together, this gender health gap is expected to amount to millions of disability-adjusted life years due to a gap in health care effectiveness for women, in care delivery, and in data that is not available that could be used in researching conditions disproportionately impacting women.

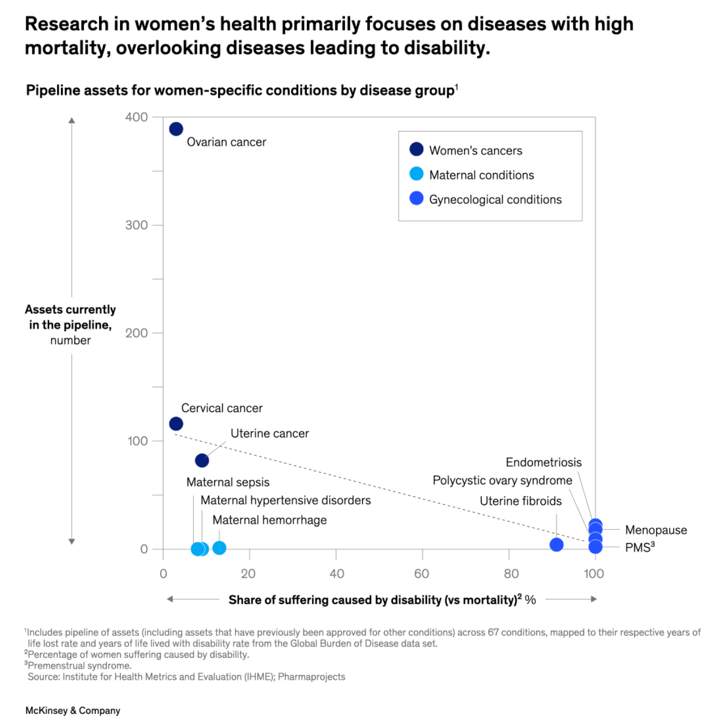

To that point, this graph illustrates research in women’s health in terms of pipeline assets — finding a clear favoring of allocating research assets toward diseases in women that impact mortality versus those impacting disability — which are those that drive the disability-adjusted life years disparity noted in the previous paragraph.

Another aspect of the female/male health gender gap related to research and pipelines is the finding that global drug withdrawals due to women’s health risks were 3.5 times greater than drugs pulled for men’s health risks between 1980 and 2023. Furthermore, on the data front, there’s a sense of “we don’t know what we don’t know” in that 34% of drug withdrawals did not have sufficient information on sex-specific adverse events to determine the possibility of further risks associated with gender.

The economic impact of gender health inequity takes a toll on a nation’s GDP: the top 10 conditions identified in this study contributive over 50% of the negative impact on GDP, including premenstrual syndrome, depressive disorders, migraine, other gynecological diseases, anxiety disorders, ischaemic heart disease, osteoarthritis, asthma, drug-use disorders, and ovarian cancer.

Women’s economic participation is a major driver of growth, McKinsey and WEF note, with better health meaning being able to work more effectively.

It takes a village to address gender health equity: the report concludes that the issue does not stand-alone — and requires the community of education, government, life science innovators, philanthropists, activists and business to recognize and address this challenge.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: More tightly focusing on the U.S. AARP conducted the organization’s annual survey of the 2024 electorate for the November Presidential and down ballot elections. AARP polled 3,380 U.S. adults, which included a group of $1,041 women ages 50 and over.

Among these women, their concerns are about the economy, retirement security, and “our democracy.”

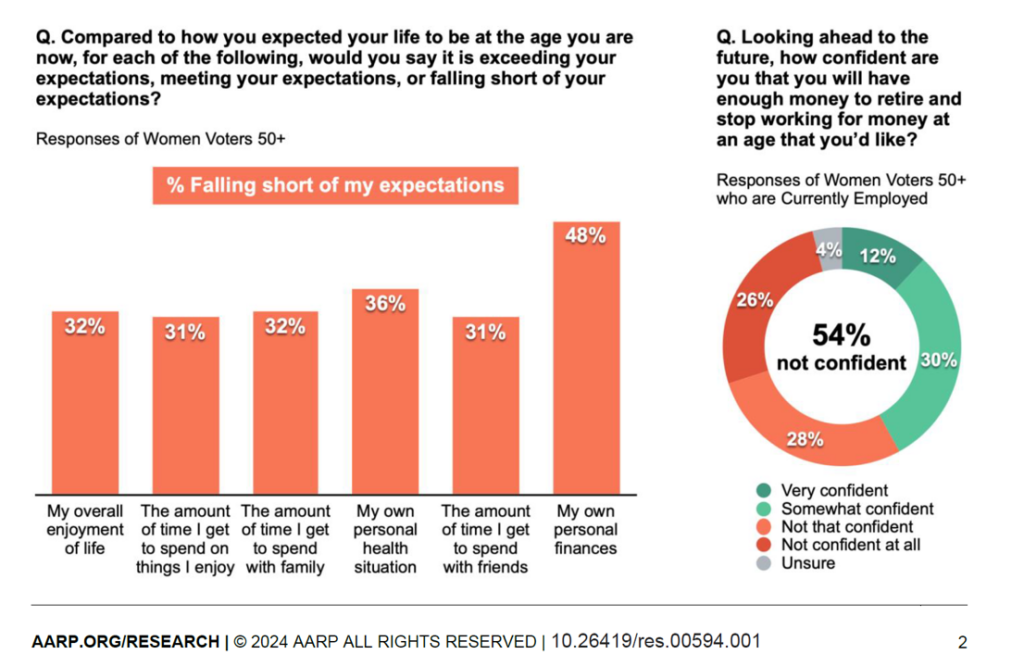

The orange and green chart here comes out of the AARP report graphing responses of women age 50+. Nearly one-half note that their own personal finances are falling short of their expectations, and 36% say their own personal health situation is falling short of their expectations.

Roughly one-in-three older women also say that they are spending less time on things they enjoy, time with family and/or friends, and overall enjoyment of life all fall short of expectations.

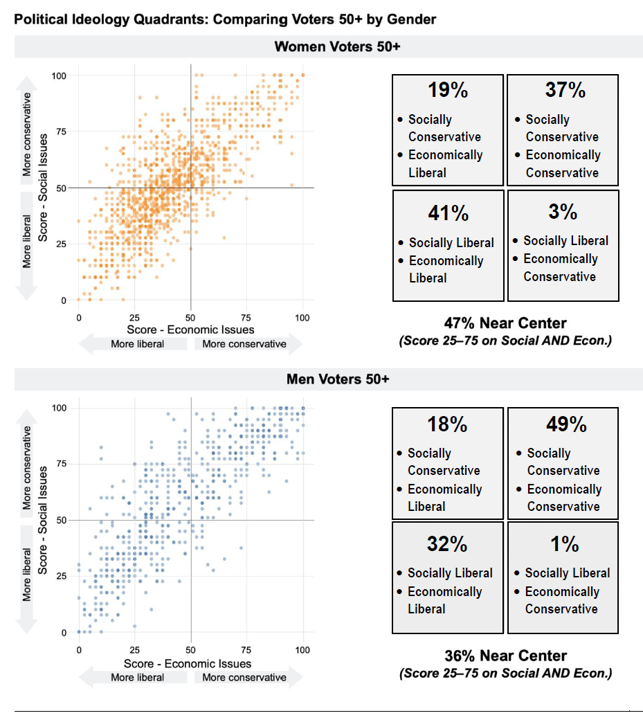

The last chart compares older voters (50+) social and economic ideologies for women and men. It’s important to note the Venus/Mars differences shown in the four quadrants for women then for men: overall, women’s social and economic views fall nearer to the center of the four quadrants than men’s: nearly one-half of women are near the center, compared with 36% of men who you can see one-half of whom are more focused on the upper-right quadrant for being conservative both socially and economically.

Catty-corner from the northeast quadrant is women’s southwest quadrant which has the plurality of 41% considering themselves socially and economically liberal.

Facing gender health issues, financial disparities at retirement, “pink taxes” on products and services for similar products men buy and consume, and taking on greater caregiving responsibilities, we should think of health care equity in the broader context of Health equity across all the pillars of well-being: indeed, physical, adding in emotional and mental health, social health and connectedness, and financial wellness. That invokes the village in a woman’s community of banks and educational institutions, retailers and business, faith institutions and town planners, and health care systems collaborating to bolster health for all.