By Daniele Palumbo, Paul Cusiac & Erwan RivaultBBC Verify & BBC Arabic

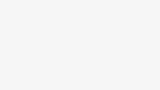

More than half of Gaza’s buildings have been damaged or destroyed since Israel launched its retaliation for the Hamas attacks of 7 October, new analysis seen by the BBC reveals.

Detailed before-and-after imagery also shows how the bombardment of southern and central Gaza has intensified since the start of December, with the city of Khan Younis bearing much of the brunt of Israel’s military action.

Israel has repeatedly told Gazans to move south for their own safety.

Across Gaza, residential areas have been left ruined, previously busy shopping streets reduced to rubble, universities destroyed and farmlands churned up, with tent cities springing up on the southern border to house many thousands of people left homeless.

About 1.7 million people – more than 80% of Gaza’s population – are displaced, with nearly half crammed in the far southern end of the strip, according to the United Nations.

Further analysis, by BBC Verify, reveals the scale of destruction of farmland, identifying multiple areas of extensive damage.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has said it is targeting both Hamas fighters and “terror infrastructure”, when challenged over the scale of damage.

Now, satellite data analysis obtained by the BBC shows the true extent of the destruction. The analysis suggests between 144,000 and 175,000 buildings across the whole Gaza Strip have been damaged or destroyed. That’s between 50% and 61% of Gaza’s buildings.

The analysis, carried out by Corey Scher of City University of New York and Jamon Van Den Hoek of Oregon State University, compares images to reveal sudden changes in the height or structure of buildings which indicate damage.

Devastation moves south

The southern city of Khan Younis has been particularly badly hit in recent weeks, with more than 38,000 (or more than 46%) of buildings now destroyed or damaged, according to the analysis. Over the past fortnight, more than 1,500 buildings have been destroyed or damaged there.

Al-Farra Tower – a 16-storey residential block in the centre of the city, the tallest building in the area – was flattened on 9 January as can be seen in before-and-after images of the city’s skyline. Much of the neighbourhood in which it sits has been levelled by Israeli attacks since late December.

“Israeli forces targeted residential complexes, especially in the downtown Khan Younis area,” said Rawan Qaddah, a 20-year-old resident, who has been displaced and has lost contact with her family.

She named schools among the many buildings which had been damaged. Some were now being used to house displaced people temporarily.

You can clearly see the level of damage from street level. Once bustling high streets have been left derelict or destroyed.

These images show the front of the Shawarma Sanabel restaurant before Israel’s invasion, and how the same junction looked in a composite image from January after intense bombardment of the area.

Extensive damage right across Gaza

The IDF has repeatedly justified its actions by noting that Hamas deliberately embeds itself in civilian areas and explained destruction of buildings in the light of targeting fighters. But questions have been asked about destruction of buildings seemingly firmly in the control of the IDF.

One example was the Israa University, in northern Gaza – initially badly damaged shortly before being blown up completely in what looked like a massive controlled explosion. The video was widely shared on social media and the IDF says the approval process for the blast is now being investigated.

Many of Gaza’s historic sites have suffered extensive damage, including the al-Omari Mosque originally built in the 7th Century.

Mr Scher, one of the academics who worked on the Gaza damage assessment, said it stands out compared with other war zones he’s analysed.

“We’ve done work over Ukraine, we’ve also looked at Aleppo and other cities, but the extent and the pace of damage is remarkable. I’ve never seen this much damage appear so quickly.”

Destruction to Gaza’s farmlands

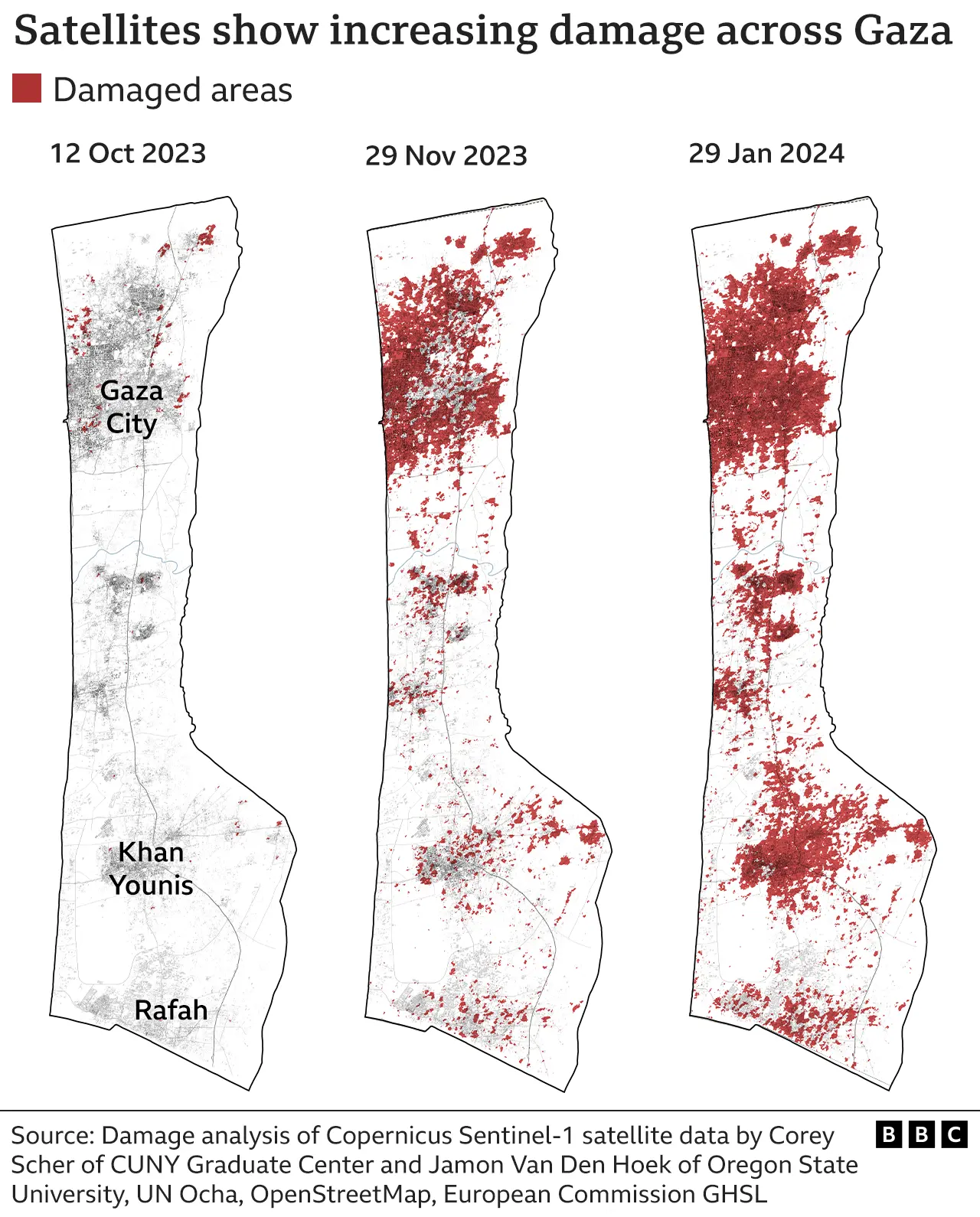

Further analysis, carried out by BBC Verify, shows large areas of previously cultivated land across Gaza have been extensively damaged.

As you can see from the satellite image below, several parts of Gaza show the effects of Israeli incursions and bombardment.

Although Gaza was heavily dependent on imports before the start of the war, a lot of its food came from farming and food production inside the strip. Aid agencies say half of Gaza’s population is now facing starvation.

BBC Arabic spoke to one farmer, Saeed, who fled south from Beit Lahia, in the north of Gaza, in mid-November.

The 33-year-old grew guava, figs, lemons, oranges, mint, and basil and earned about $6,000 (£5,535) from these crops every year – the only source of income for him, his father and his sister. He had tended to the farm, inherited from his grandparents, for 15 years.

But days after fleeing, he says he was told by a relative that the farm had been destroyed by the IDF, along with five surrounding homes which belonged to his relatives.

In the north and centre of Gaza, where most agriculture took place before the war, large areas of land appear ruined. In many places the damage corresponds with the construction of temporary Israeli defences, earth banks to protect armoured vehicles, and the clearing of surrounding land.

Some farmers have lost their crops even though their land was not directly hit, the BBC understands.

Mohamed al-Messaddar, a farmer from Deir al-Balah in central Gaza, has only been able to go to his farm once since the beginning of the war.

Arriving during the truce in November, oranges were scattered, rotting on the ground. “The date of harvesting oranges coincided with the beginning of the war. No one would have dared to go there.”

He says he lost more than 90% of his orange crop.

Beyond the pattern of land affected by bulldozing of roads and building of defences, there have been allegations of deliberate destruction levelled at the IDF.

In a video posted online on 4 November, Col Yogev Bar-Shesht, deputy head of the Civil Administration, said in an interview from inside Gaza: “Whoever returns here, if they return here after, will find scorched earth. No houses, no agriculture, no nothing. They have no future.”

The IDF told us it had found Hamas tunnel entrances and rocket launch sites in various agricultural areas, adding that “operational needs require that these places be destroyed or attacked”.

“Environmental damage may be caused as a result of fighting and exchanges of fire.”

Aid experts fear that the damage to Gaza’s agriculture will be lasting.

Previous conflicts such as those in Syria and Ukraine have shown rehabilitating farmlands can be extremely difficult.

Unexploded weapons make it dangerous for farmers to return and work. There’s also the challenge of cleaning contaminated lands, and rebuilding infrastructure such as water, energy and transport systems.

City of tents emerges

The final pronounced change in Gaza that can be seen from the air is the proliferation of tents and other temporary structures to house displaced people in the south.

Areas of new tents that have sprung up between the start of December and middle of January close to the Egyptian border covered roughly 3.5 sq km, equivalent to nearly 500 Premier League football pitches.

The satellite images, captured on 3 December and 14 January, show a dramatic change – now nearly every patch of accessible, undeveloped ground in an area of north west Rafah has been turned into a refuge for displaced people.

When it launched its campaign against Hamas, Israel told Palestinians living in north and central Gaza to move south for their own safety. Many have ended up in Rafah and face an uncertain future.

Additional reporting by Jake Horton, Benedict Garman, Tural Ahmedzade, Kate Gaynor, Lamees Altalebi, and Abdelrahman Abutaleb.