No one knows exactly how much damage the coronavirus will do to the global economy, but investors have to guess.

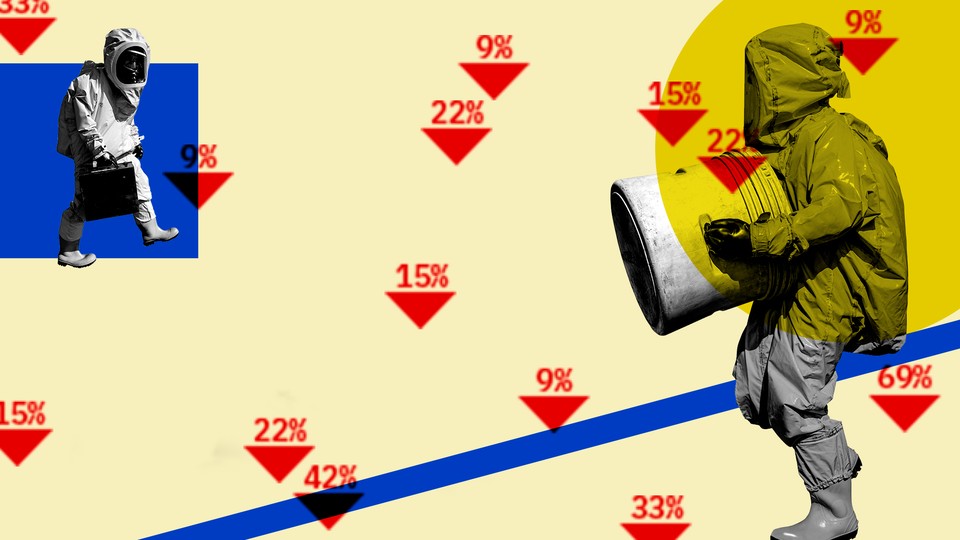

Over the past week, stock markets around the world plunged as distressing news about the spread of the novel coronavirus continued to accumulate. In the United States, the three major stock indexes—the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the Nasdaq Composite, and the S&P 500—fell more than 10 percent below their recent peaks, a sharp decline that qualifies in Wall Street terminology as a market “correction.” One investor quoted in The Wall Street Journal called it a “bloodbath.”

The global stock market is, theoretically, the distillation of how investors think everything that happens in the world will play out in the economy. Right now, judging by these drops, investors are much less optimistic than they were a week ago. But what they’re predicting is not only how bad the outbreak could be in terms of workers staying home sick, drops in consumer spending, or supply-chain disruptions; it’s also how bad people think it could be. Those might turn out to be two very different things.

Read: You’re likely to get the coronavirus

Public perception of a crisis can be extremely consequential in financial markets. “The notion of a pandemic is pretty scary to people, and they’re going to hunker down and be careful about how they live their lives” if bleak news continues to roll in, says Richard Sylla, a former professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business. They may, for instance, start to skip vacations or dine out less. Airlines and restaurants, in turn, might lose revenue or even limit service because of what they think their customers will do. All of this combined would carry negative consequences for the economy, regardless of how catastrophic the direct impact of the disease actually turns out to be. “What people are thinking, even if it’s wrong, maybe matters more on a day-to-day basis [in the stock market] than what the truth is,” Sylla said.

What investors think the public is thinking is therefore crucial. Whether the costs of the outbreak turn out to be historically large or not, there is a risk that investors’ worries will snowball during this period of uncertainty, leading them to panic-sell and exacerbate any financial damage. “If in the next 20 years [the economy is] only going to be disrupted for three months, that suggests a very small impact on the market,” says Robert J. Shiller, a Nobel Prize–winning economist and the author of Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events. But the situation could be much worse, and when investors think in “grandiose terms,” Shiller told me, that could “trigger other worrying.”

Predicting the emotional reactions of the entire world population to coronavirus would be a bit easier if investors could turn to the market effects of previous pandemics for guidance. But history provides few indications of what might happen to the economy if the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease it causes, continue to spread. “This is kind of a new thing,” Shiller said. “It’s too much to ask for the market to get it right.”

The closest analogue is the global influenza outbreak of 1918 and ’19, which killed tens of millions of people. In 1918, the stock market actually did fine—the Dow rose a little. In the years after that, Sylla noted, “the stock market didn’t do much, and while its trend was flat, there were fluctuations within that—some ups and downs, just like we see now.”

But drawing any conclusions from 100 years ago is difficult because, among other reasons, a lot of other stuff was happening then—namely, World War I. Because of that, says John Wald, a professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio’s College of Business, “it’s really hard to say whether [the 1918 pandemic] was priced correctly or not correctly” by the market.

Perhaps a better parallel is the flu pandemic of 1957 and ’58, which originated in East Asia and killed at least 1 million people, including an estimated 116,000 in the U.S. In the second half of 1957, the Dow fell about 15 percent. “Other things happened over that time period” too, Wald notes, but “at least there was no world war.” More recent outbreaks, such as SARS and MERS, were more contained and didn’t wreak as much global economic havoc.

Although the annual flu season is quite different from a pandemic, it does provide a good amount of data for economists to analyze. When Wald, along with the researchers Brian McTier and Yiuman Tse, examined trading records from 1998 to 2006, they found that in weeks when the flu was more widespread, stock-market returns were lower. They also found that when there was a higher incidence of the flu in the greater New York City area in particular, trading volume decreased, which is usually bad for the market. Here, the idea is that more professional investors might have gotten sick and executed fewer trades—which would not bode well if COVID-19 were to make its way to New York City.

Sylla’s view of all this as a financial historian is pretty zen. “I wouldn’t pay much attention to the day-to-day reports of the newspapers—‘Here’s a good sign,’ ‘Here’s a bad sign,’” he said. In the short run, the stock market isn’t necessarily a good predictor of how bad the pandemic will get, in part because investors are working off the same scant information as everyone else. “What I would say history shows you is that a problem like this takes many months and maybe even a couple of years to play itself out,” he said. But, he went on, “Wall Street’s idea of history is the last 10 minutes.”